Scotch Tasting: Guide to Whisky Terms

After attending several Scotch Whisky tastings, I learned to better appreciate the history and process of making Scotch Whisky; I’ve compiled a summary of some basic concepts and terms. You can read this unaccompanied, however it would be more enjoyable to absorb while indulging in a good dram of the finer spirits produced by Scotch master blenders.

Remember, everybody’s tastes are different. Your palate, your whisky!

What is Scotch Whisky?

Scotch Whisky is a category of whisky made in Scotland from a mash bill of three simple ingredients: water, cereals, and yeast. Scotch was distilled as early as the 15th century, when first called uisge beatha, “aqua vitae”, or “water of life”. Over time, “uisge beatha” was shortened to simply “uisge” – which sounds like “oosh-gae”.

While not initially a protected spirit, Scotch Whisky has been defined by statute in the United Kingdom since 1933. The legal definition set out in the Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009 (“the UK Law”) defines Scotch Whisky as:

- Made in Scotland from ONLY cereals, water, and yeast

- Matured for a minimum of 3 years in oak casks (< 700L)

- Bottled at a minimum strength of 40% abv

- Distilled below 94.8% abv – to retain the flavour and aroma derived from its raw materials

- NO flavouring or sweetening is permitted (plain caramel colouring is allowed)

How is Scotch Whisky Made?

Malt whisky production begins by steeping barley in water, spreading it out on a malting floor, then mashing it. The malt is dried in a kiln, which halts germinations, preserving the natural sugars produced during malting. During this process, the kiln may be fired by natural gas or by burning peat – which contributes a smoky flavour. Once dried, the malt gets turned into a flour-like grist using a rolling mill. The grist is moved to a mash tun where is it mixed with hot water. The resulting sweet liquid is called wort which is then cooled, filtered, and added to washback’s, also known as containers, made from wood or stainless steel. Fermentation begins once yeast is added to the washback. The live yeast feeds on the sugars to produce alcohol while also burping out carbon dioxide. The resulting liquid is a beer-like solution called wash which is then distilled twice in single-batch pot stills. The heart of the resulting liquid goes into oak casks, where the maturation process begins.

Grain whisky goes through a similar process which typically includes some malted barley. Any non-malted cereals, typically wheat, are precooked and added to the mash bill. The mashing and fermentation process for grain whisky is like that of malt whisky, but the wash is distilled in a continuous or Coffey still before transferring to oak casks for maturation. Most matured grain whisky is used in blending with Blended Scotch or Blended Grain Whisky; accounting for upwards of 90% of Scotch Whisky production.

Types of Scotch Whisky

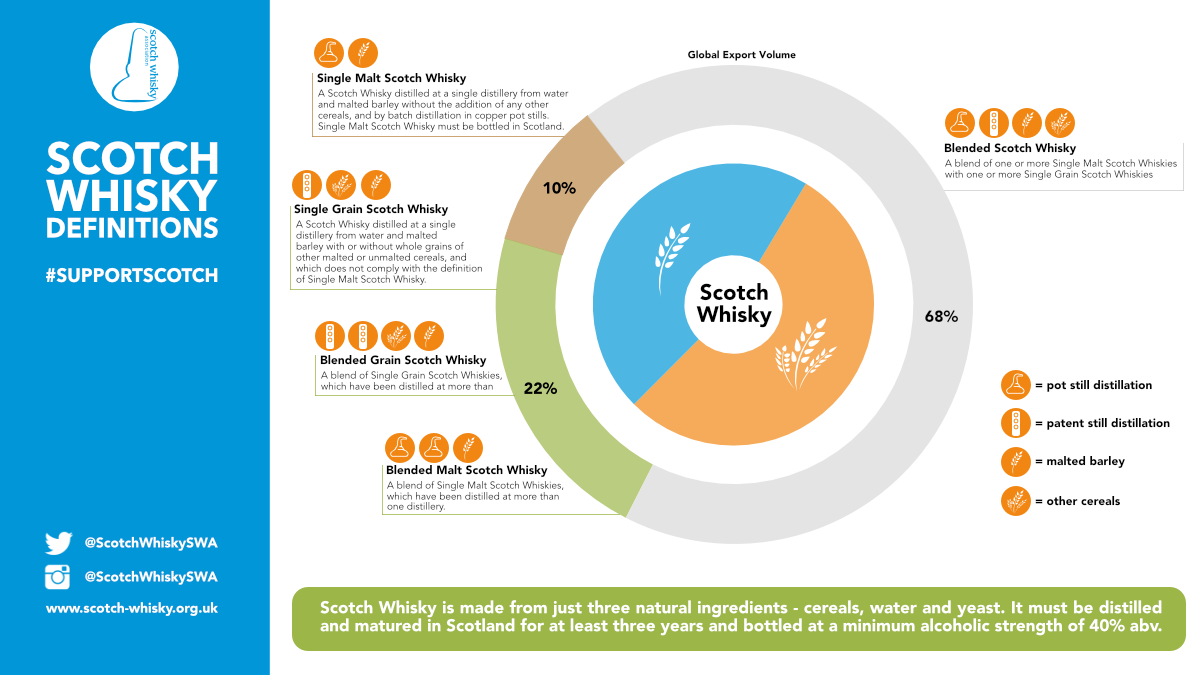

According to UK law, there are five (5) categories of Scotch Whisky:

Single Malt

Distilled from water and malted barley in one or more batches at a single distillery in copper pot stills without the addition of any other cereals. Single Malt Scotch Whisky must be bottled in Scotland and accounts for just 10% of Scotch Whisky production.

Blended Malt

A blend of two or more Single Malt Scotch Whiskies that have been distilled at more than one distillery.

Single Grain

Distilled from water and malted barley with or without whole grains of other malted or unmalted cereals at a single distillery. Single Malt and Blended Malt Scotch Whiskies are exceptions to this category.

Blended Grain

A blend of two or more Scotch Grain Whiskies that have been distilled at more than one distillery.

Blended Scotch

A blend of one or more Single Malt Scotch Whiskies with one or more Single Grain Scotch Whiskies.

The five types, along with their global export percentages are shown in the graphical visualization below:

Useful terms to know:

Dram

A dram is a single serving of whisky. The exact definition varies by country/region, but the Scottish definition is the amount of whisky that fits into “dram measurers” or 1/13th of a pint, approximately 42mL. Colloquially, it simply refers the size of the pour in the glass – hence the quaint expression “a wee dram of whisky”.

Colour

You can learn a lot about a whisky just by looking at it. Before nosing or tasting a whisky, examining its colour can help set the expectations for aromas and flavours to follow. While expectations are not always matched, it’s fun to gauge if the nose and palate will meet the expectations developed while studying the colour.

Nose

Simply, this is the scent of the whisky. Slowly bring it up to your nose and make a brief introduction with a small sniff and acclimatize your nose. Some whiskies have an overwhelming burning sensation from the alcohol. That initial sniff preps the senses for a deeper, nose diving, second whiff during which you may be able pull out subtle aromas. Most of what we classically associate with taste is actually smell.

Palate

Taste the whisky, your whisky! Start with a sip and let the spirit coat your tongue. Contrary to common belief, there are not tasting regions on your tongue so let the liquid expression spread everywhere and note any tastes that come to mind. There are only 5 tastes – sweet, sour, bitter, salt, and umami – while there are thousands of distinct aromas that may be detected while nosing and tasting a whisky.

Finish

This describes how long you continue to taste flavours after finishing your sip. If the flavours are fleeting, it is called a short finish. Flavours that go on and on are known as a long finish and when flavours last somewhere in the middle, it’s a medium finish.

A sample tasting sheet from The Scotch Malt Whisky Society (SMWS) is shown below to capture all the smells, flavours, and memories that you may experience from each dram:

Cask

Casks are containers used for storing whisky during the maturation process; they are made of oak using staved timber bound by closed metal hoops. Casks come in many sizes and shapes resulting in different amounts of the whisky surface exposed to the wood – imparting additional flavours and character. By law, Scotch Whisky must be aged in oak casks for a minimum of three years.

Cask Finish / Finishing

Oftentimes a distiller will transfer matured whisky from one cask to another, “finishing” the maturation in a second cask for a shorter amount of time and imparting different flavours to finish a whiskies education. Second casks are often containers that previously held liquids such as bourbon, rum, wine, or sherry (oloroso or PX).

Hogshead

A hogshead was once a measure for wine and ale. These are mid-size casks ranging from 230-250L and are quite common for maturing whisky these days. Larger cask dimensions mean less surface area comes in contact with the maturing spirit, allowing for a longer maturation period.

Quarter casks

These casks are about a quarter of the size of a hogshead or standard barrel, making them about 40-60L. Smaller casks offer more interaction with the wood allowing more flavours, such as oak, butter, and vanilla to be imparted over longer periods of maturation. This is also the namesake of one of my go-to bottles from Laphroaig.

Butt

Famously used to mature sherry, Butts have 500L capacity and tend to be the larger casks in a dunnage warehouse. That is a butt-load of whisky!!

1st Fill

Refers to the number of times a cask has been filled and used to mature whisky. 1st fill casks are virgin casks freshly assembled and used to age Scotch for the first time. They may have previously been flavoured with and used to age Bourbon, Sherry, Wine, Port, Rum, or even Tequila.

Refill

Refill casks are containers used to age whisky that have been used 2 or more times. When used a second the cask is often referred to as a 2nd fill. Sometimes casks are toasted or charred on the inside to rejuvenate them allowing the whisky to extract as much remaining aroma and flavour notes from the wood as possible.

Maturation / Maturing

After distillation, whisky is stored in oak casks. Although barrels are liquid tight, air still manages to pass through the wood allowing oxygen to contact the spirit inside the barrel. This interaction during maturation allows the original compounds in the whisky to oxidize and impart flavouring compounds from the wood.

Longer maturations mean more oxidation and interaction with the wood. Sometimes this is a good thing and sometimes maturing takes a whisky beyond its prime. Older whiskies are not necessarily better, but generally cost more as there is a storage fee and angels share that must be recovered for longer maturations.

Cooper / Coopersmith

Coopers are the woodworkers of the whisky world. You may already be familiar with the surname Cooper. In medieval times, it was common practice to define people by their profession, giving us surnames such as Baker, Smith, Potter, or Taylor. Coopering is the act of making or assembling a wooden, staved vessel with flat ends that is bound together with metal hoops.

As the wood from casks not only changes the colour of the spirit, it also impacts the flavour by skillfully removing the rough edges. It’s during the maturation that young, untamed spirits develop into something more sophisticated and expressive. Some distillers claim that an oak cask is responsible for up to two-thirds of a whisky’s flavour. For this reason, the art of coopering remains one of the most important crafts in creating a quality whisky.

Angel’s Share

During the aging process in casks, distillate slowly evaporates through the wood. More evaporation occurs while the whisky is young in the barrel and slows down as it ages. Distillers justify this loss as a sacrifice to the heavens believing that giving the angels their share will ensure the whisky is the best it can be when it’s bottled.

ABV

ABV, or “alcohol by volume”, is measure of how much pure alcohol, or ethanol, is contained in a liquid. Proof statements are simply the ABV value doubled. Scotch Whisky must contain a minimum of 40% (or 80 proof) alcohol by volume. Historically, seaman would ‘proof’ a spirits strength using gunpowder. If the alcohol content was over 50%, the gunpowder would ignite, and overproof Rum would happily be accepted.

Cask Strength

Usually, whisky is diluted with water before bottling to bring it down to 40% ABV and produce more product for retail shelves. Cask strength whisky is bottled at the strength at which it’s drawn from the cask. While aging, whisky develops a symbiotic relationship with the cask. As the liquid seeps in and out of the wood grain, these casks tend to impart intense, robust flavours – the hallmarks of cask strength whisky. Typically, cask strength whisky has an ABV ranging anywhere between 50-75%. Cask strength whisky tends to stand up when adding water.

Age Statement

The age statement of a whisky must reflect the age of the youngest whisky blended. Due to evaporation, a 20-year-old spirit might lose upwards of 40% of its volume by the end of its maturation period. Older whiskies often cost more, not necessarily because they are better, but because they must be stored longer, and significant amounts of product are lost to the angels.

Some whiskies have no age statement (NAS), which is something that has become increasingly common in recent years. Distillers are not required to place an age statement on the bottle and as a result, some have argued this is a lack of transparency. As a blended whisky’s age statement must reflect the age of the youngest whisky used, others counter that age statements do not reflect the quality of the spirits inside the bottle. There are many age-snobbists who will not give a bottle a second glance if it is under 18 years, erroneously thinking older means better.

Peated

Peat is sometimes used to fuel the fires used during the drying process to stop germination in malted barley. When burning this fossil fuel – often consisting of slow decomposing moss, grass, and tree roots – compounds in the peat smoke are absorbed by the barley contributing to smoky flavours – typically described as tar, ash, iodine, or smoke. Peat bogs are not available everywhere and many distilleries use natural gas.

PPM

Phenolic parts per million (PPM) is a measure of the phenol content of whisky after kilning. Phenols are released when peat is used to fuel the kiln during the drying process often contributing to the smoky flavour found in some whisky. The higher the PPM, the peatier the whisky will taste. Heavily peated whiskies will have a PPM in the range of 40 – 70. Bruichladdich’s Octomore 8.3 is the highest PPM whisky made so far with a beyond category (HC) PPM of 309 – so peaty, it tastes smooth.

Water

Most whisky is watered down to 40-46% before transferring from cask to bottle. This is done to replace some of what was lost to the angels share and more practically – to yield more product for retail shelves. The water added can pass along its own flavours based on mineral content. Enjoyers of fine Scotch Whisky can also add water to their glass to bring out different tones and flavours. Never be afraid to add water to dilute your whisky to your personal tastes.

Column (Coffey) Still

The first Scottish distillery to install a Coffey Still was the Grange Distiller, which closed its doors in 1851. Patented by Aeneas Coffey in 1860, a Coffey or column still consists of two stainless steel columns, capable of continuous distillation. The column is composed of a series of plates or trays. Each tray is slightly cooler than the one beneath it causing a bit of condensation to form on each tray which in turn is redistilled and thrown back into the vapour state due to the heat rising from below. This allows for more efficient and cost-effective production of grain Scotch whiskies. Column stills tend to produce a purer, cleaner distillate than pot stills.

Pot Still

Pot stills are typically made of copper and are used as a distillation vessel on a batch-by-batch basis. Some distillers are superstitious and will go to great lengths when rebuilding copper pot stills to ensure every dent and bump is replicated to keep the whisky taste constant over the years. Pot stills are single batch productions requiring significant cleaning in between productions. All single malt whiskies must be made in a pot still as they tend to produce a more flavoursome spirit, richer in congeners.

Regions of Scotch

According to The Scotch Whisky Regulations of 2009, Scotland is divided into two protected localities – Campbeltown and Islay: along with three protected regions – Highland, Lowland, and Speyside. There is also a sixth, unofficial region referred to as the Islands.

Speyside

The most densely populated Whisky region in the world is found in the fertile rivers, bens (hills), and glens (valleys) of the Speyside region. Whiskies produced from this region expose lavish fruit and nutty flavours often found in apple, pear, honey, vanilla, and spice. Several Speyside whiskies have found their way into Sherry casks for a finish that adds the rich, deep, fruit flavour of figs and raisins along with mouth drying sulphur notes.

Islay

A wind swept and barren whisky island on the southwestern coast of Scotland known for its heavily peated whiskies. Peat covers much of the island and was often used to fuel the fires providing heat during the malting process. Islay expressions typically present with smoke, brine, or pungent peat slowly revealing their layers of complexity which could be anything from the sea, forest floor, or a mechanic shop.

Campbeltown

The smallest whisky region is found on the peninsula of the Campbeltown locale. Production and maturation are heavily influenced by the seaside locations known for distinctive whiskies that show off flavours with smoky, oily, and briny notes.

Highlands

The Scottish Highlands cover a vast geography ranging from wild seas to impenetrable moorland along with mountain peaks and secluded lochs. As such, the whisky in this region varies widely from full-bodied peaty drams while other expressions show off heather and silky elegance with hints of nuts and honey.

Lowlands

The Lowlands sit just above England at the southern edge of Scotland. Whiskies from this region are typically characterized as soft and gentle malts – making them great gateway whiskies for those starting their journey into the world of Scotch Whisky with mellow palates reminiscent of grass, honeysuckle, cream ginger, toffee, toast, and cinnamon. Like many Irish whiskies, some Lowland malt whiskies are triple distilled, again resulting in lighter and softer expressions.

Islands

Not officially recognized as a distinct region or local, the Islands consist of Maritime locations, often found with polarizing expressions. Due to the vast differences on each of the islands, flavours can include anything from: brine, oil, black pepper, nuttiness, heather, and honey.

Whisky Making Process

Malted Barley

Barley is a grain commonly used in breads, soups, or stews. Grains are little starch containers and can be coerced to covert starch into sugar by soaking them in water to initiate germination. Before sprouting and when sufficient starch has been converted to sugar, germination is halted by removing water and exposing the grain to heated air. This dried and partially germinated grain is known as malted barley.

Kiln

A kiln is an oven, furnace, drum, or vessel used for drying malted barley using hot air. Sometimes peat is burned to produce the drying heat and the smoke is absorbed by the malt, contributing a peat or smoke flavour to the final product.

Mash Tun

Malted barley is coarsely ground up or milled into a grist and hot water is added to dissolve the sugar produced during partial germination. The combination of grist and hot water is called a mash which resembles a porridge like mixture. A mash tun is the vessel used to hold the mash where it can be mixed to speed up and control the process of washing and filtering the sugar liquid into a huskless water (or wort).

The filtered husks are a waste product of the whisky making process and are made into feed pellets for livestock breeding. Nothing goes to waste in the whisky making process.

Wort

Wort is the sweet, fermentable, huskless, sugar water produced in the mash tun.

Fermentation

Yeast does not tolerate high temperatures, so the wort must be cooled down to around 20°C before adding the yeast. Adding yeast to the wort allows the sugar to be converted into alcohol via a fermentation process. This new wort-yeast mixture is known as the wash. Washbacks are the vessels used to hold the wash during fermentation.

Fermentation is an exothermic (heat producing) chemical reaction where the yeast (a fungi) feeds on sugar in the wort – burping out carbon dioxide and pissing out ethanol (alcohol – the desired product).

The length and temperatures of the fermentation process can influence the flavours of the final product. Depending on the distillery, the process can take anywhere from 48-96 hours.

At this point, we essentially have beer or underdeveloped whisky.

Wash

Wash is the beer-like liquid resulting from the mixture of living yeast and wort (mixture of dried malt and hot water).

Distillation

Distillation is the process of separating different substances via heating. At standard air pressure (14.69 psi or 1013 hPa), ethanol vaporizes at 78.5°C and thus the alcohol molecules evaporate before the water molecules. Single batch pot stills or continuous column stills are used to heat the wash. Rising ethanol vapor is then passed through a condenser, producing a liquid with a higher ABV concentration.

After the first distillation, the condensed liquid is sometimes called the “low wine” (20-25% ABV) which is then passed through a second distillation process. The second still is sometimes called the spirit still. Final distillate (new make spirit) is raw and must be transferred to oak barrels for maturation or is sometimes passed through a third distillation process and then transitioned to barrels for aging.

The left-over solution in the pot still (called ‘pot ale’ or ‘spent wash’) has a very low alcohol content but contains valuable proteins and minerals. This solution is concentrated via evaporation and sold-off as high-quality animal feed.

Chill-filtered

All whisky is filtered before bottling to remove any particulate matter picked up from time maturing in the barrel. Chill-filtration is a more meticulous process, often criticized as it can remove chemical compounds like fatty acids that bind together at low temperatures. Fatty compounds are believed to add flavour and texture to the spirit. Removing those compounds can obviously change a whisky’s palate and mouth feel, hence the criticism. Non-chill-filtered whiskies may still contain fatty compounds which can create an undesirable cloudiness or haze in the whisky, however flavour and feel remain intact.

Hopefully this is enough terms and concepts to get you started in the world of whisky production and tasting, so pour yourself another dram and appreciate all the work that went into crafting the refined spirit in your glass!

Slàinte!

Resources

Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2009/2890/contents/made

UK Law – Defining Scotch

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2009/2890/regulation/3/made

The Scotch Malt Whisky Society (SMWS) Tasting Mats

https://www.smws.ca/tastings-events/home-tasting/

Maturation in Casks

https://www.whisky.com/information/knowledge/production/details/maturation-in-casks.html

10 Common Types of Whisky Casks